Student loans are packaged together and then sold as financial securities, just like auto loans and credit card debt and home mortgages. These asset-backed securities pay a return to their investors as the debts are repaid. If outstanding students loans were to be cancelled, then the investors in this securities would probably be bailed out by the federal government–which was closely involved in securitizing these loans in the first place, and does not want to get a reputation for reneging on its debts. If such a debt cancellation happened, how would the benefits be distributed? Adam Looney tackles this question in “Student Loan Forgiveness Is Regressive Whether Measured by Income, Education, or Wealth: Why Only Targeted Debt Relief Policies Can Reduce Injustices in Student Loans” (Brookings Institution, Hutchins Center Working Paper #75, January 2022).

One basic insight of the paper is that those who have college degrees will tend to have, on average, more income, education and wealth over their lifetimes than those who do not. An additional insight is that many of the biggest student loan debts are not incurred by someone trying to pick up some career training at the local community college, but rather by those borrowing to finance advanced postgraduate degrees in areas like medicine and law. Thus, Looney writes:

There is no doubt that we need better policies to address the crisis in student lending and the inequities across race and social class that result because of America’s postsecondary education system. But the reason the outcomes are so unfair is mostly the result of disparities in who goes to college in the first place, the institutions and programs students attend, and how the market values their degrees after leaving school. Ex-post solutions, like widespread loan forgiveness for those who have already gone to college (or free college tuition for future students) make inequities worse, not better. That’s clearly true when assessing the effect of loan forgiveness: the beneficiaries are disproportionately higher income, from more affluent backgrounds, and are better educated.

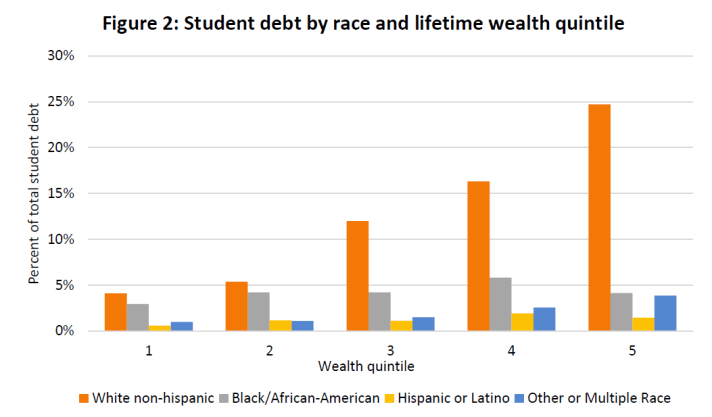

For example, here’s a calculation by Looney of who holds student debt, broken down by lifetime wealth and by race. By far the biggest share of student loans is held by white non-Hispanic borrowers who over their lifetimes will be toward the top of the wealth distribution.

Looney readily acknowledges that student loans can be a substantial burden for certain borrowers. He writes:

There is no doubt that one of the most disastrous consequences of our student lending system is its punishing effects on Black borrowers. Black students are more likely to borrow than other students. They graduate with more debt, and after college almost half of Black borrowers will eventually default within 12 years of enrollment. Whether measured at face value or adjusted for repayment rates, the average Black household appears to owe more in student debt than the average white household (despite the fact that college-going and completion rates are significantly lower among Black than white Americans). One reason for the disparity is financial need. Another is the differences in the institutions and programs attended. But an important reason is also that Black households are less able to repay their loans and are thus more likely to have their balances rise over time. According to estimates by Ben Miller, after 12 years, the average Black borrower had made no progress paying their loan—their balance went up by 13 percent—while the average white borrower had repaid 35 percent of their original balance. These facts certainly constitute a crisis in how federal lending programs serve Black borrowers.

But deciding to cancel all student loans–including those taken out by the doctors and lawyers of the future–would be an absurdly expensive and overly broad approach to reducing racial disparities or in general helping lower-income people struggling with student debt. Some targeting is called for.

As one example, Looney suggests expanding Pell grant programs that provide grants, not loans, to low-income students. It is also possible to expand the programs that tie student loan repayment to income. My own sense is that if there is a political imperative for forgiving some student loan debt, it should be focused on debt incurred for undergraduate studies, limited in size, and linked to income: for example, a program for the federal government to pay off up to $10,000 in undergraduate student loan debt for those with the lowest income levels could make a substantial difference to those who (perhaps unwisely) ran up loans they could not readily repay, without being a bailout for those who are going on to well-paid careers.